A few weeks ago I was craving a math puzzle but feeling uninspired, so I turned to the Equational Theories project for ideas. The project (which has now come to an end) aimed to prove as many implications as possible between algebraic identities of binary operations by crowdsourcing proofs written in the Lean programming language. In its completed state, the project is not only an incredible accomplishment but also a great source of mathematical chestnuts.

I settled on spending some time exploring central groupoids, which are defined as magmas (i.e. sets equipped with a binary operation $\cdot$) satisfying the following law: For intuition, there's a whole family of easy-to-comprehend central groupoids that can be defined on sets of ordered pairs $A^2 = A\times A$. On a set of this form, the operation defined by $(x_1,x_2)\cdot (y_1,y_2) = (x_2, y_1)$ automatically satisfies the central groupoid law. Central groupoids of this form are called natural central groupoids. Part of the intrigue of central groupoids is that it's kind of tricky to exhibit families of non-natural central groupoids that are as intuitive as the natural ones. Even non-natural central groupoids have several properties that are loosely analogous to the central ones: for instance, all finite central groupoids have a perfect square number of elements (which we will prove later).

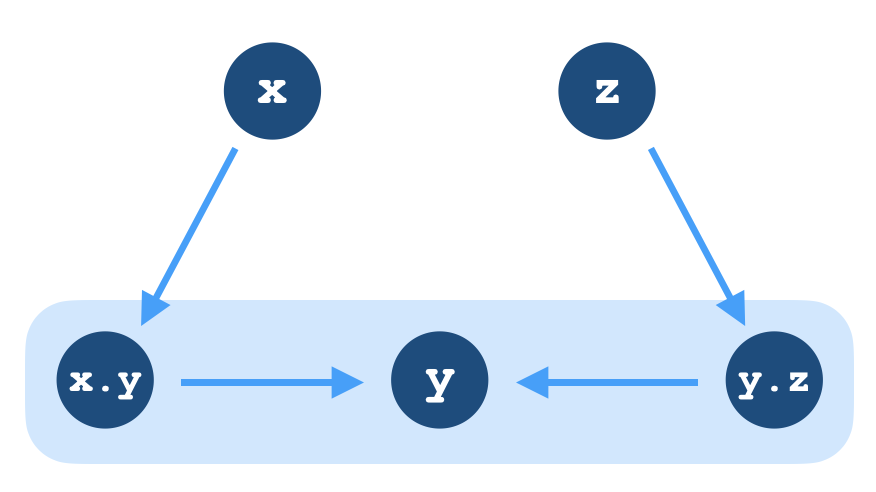

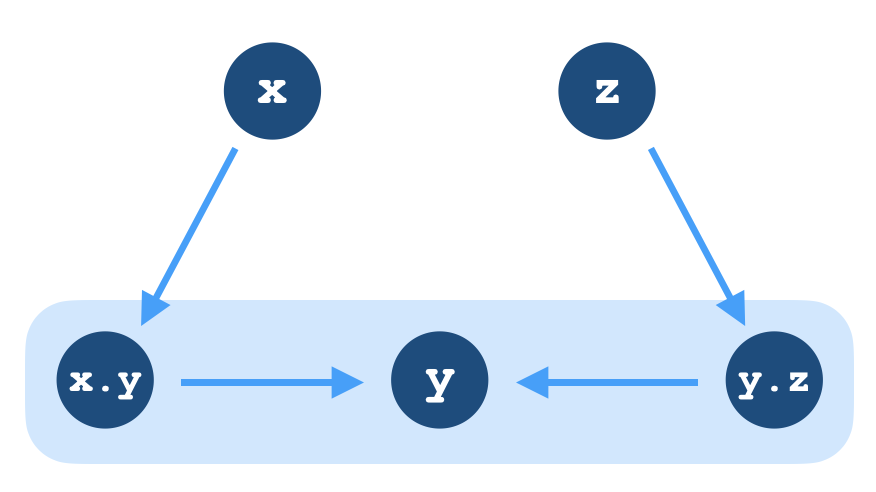

Central groupoids can also be understood as a special kind of directed graph. If $D$ is a digraph with the property that any two vertices $v,w\in V(D)$ have a unique directed path of length 2 between them, then a binary operation $\cdot$ can be defined on $V$ such that $v\cdot w$ is the intermediate vertex on that unique path, that is, the unique vertex such that $v\to v\cdot w \to w$ in the graph $D$. It follows that this binary operation satisfies the central groupoid law: if $x,y,z\in V(D)$, then $x\cdot y\to y$ and $y\to y\cdot z$ are both edges, meaning that $y$ is intermediate on a path of length 2 between $x\cdot y$ and $y\cdot z$.

Conversely, every central groupoid arises from a digraph in this way, and given a central groupoid $C$ we can construct a digraph $D$ giving rise to it. Simply let the vertices $V(D)$ consist of the elements of $C$, and for each vertex $v\in V(D)$, let there be an edge joining $v\to v\cdot w$ for each $w\in V(D)$. This graph is guaranteed to have the uniqueness property of length-2 paths: if $v\to x\to w$ for some $v,w,x\in V(D)$, then we must have that $x = v\cdot v'$ and $w = x\cdot w'$ for some $v'$ and $w'$, implying that $(v\cdot v)\cdot x = v$ and hence $v\cdot w = x$, meaning that all intermediate elements on a length-2 path from $v$ to $w$ must equal $v\cdot w$.

Digraphs $D$ can also be represented by incidence matrices $M$, that is, sets of 0s and 1s such that a value of 1 in row $i$ and column $j$ indicates and edge $i\to j$ in the digraph. The length-2 path uniqueness property in the digraph $D$ for a central groupoid has a neat translation into matrix language: it's equivalent to $M^2 = J$, where $J$ is a matrix of all 1s. So central groupoids also correspond to zero-one matrices whose square is the identity matrix.

When working with concrete examples by hand, I find a different representation of central groupoids more convenient, since drawing out digraphs gets messy very quickly. A central groupoid $C$ can also be represented by a function $f: C\to \mathcal P C$ — that is, an assignment of a subset of $C$ to each element of $C$ — with the special property that for each subset $f(x)\subset C$, the set ${f(y) ~ : ~ y\in f(x)}$ comprises a partition of $C$. In terms of the central groupoid operation, the set $f(x)$ would be the set of all left-images of $x$, that is, the set of values $x\cdot y$ for $y$ ranging over $C$. In terms of the digraph representation $D$ for the central groupoid $C$, for a vertex $v\in D$, the value $f(v)$ would give the set of all vertices that are the target of an edge originating from $v$.

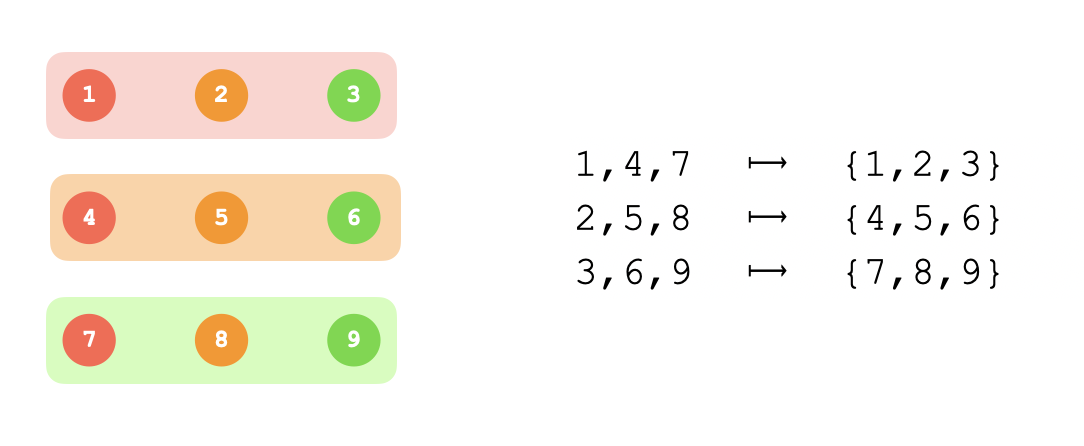

There's only one central groupoid of order 4, namely the natural one, so let's look at a couple concrete examples of order 9. Here's how I visualize the natural central groupoid of order 9. On the right is a table describing the function $f$, which maps each $x\in C$ to a subset of $C$. On the left is how I picture the digraph representation of $C$ without drawing a tangled mess of edges: for each vertex, the color of the vertex indicates that it should have directed edges pointing to each vertex in the set of the same color. For instance, $v_1$ has outward-pointing edges $v_1\to v_1$, $v_1\to v_2$ and $v_1\to v_3$ because it is red, and the red-colored group contains vertices $v_1,v_2,v_3$.

Values of the central groupoid operation can be read off from these diagrams. To compute, for instance, $v_1\cdot v_5$, you can follow these steps:

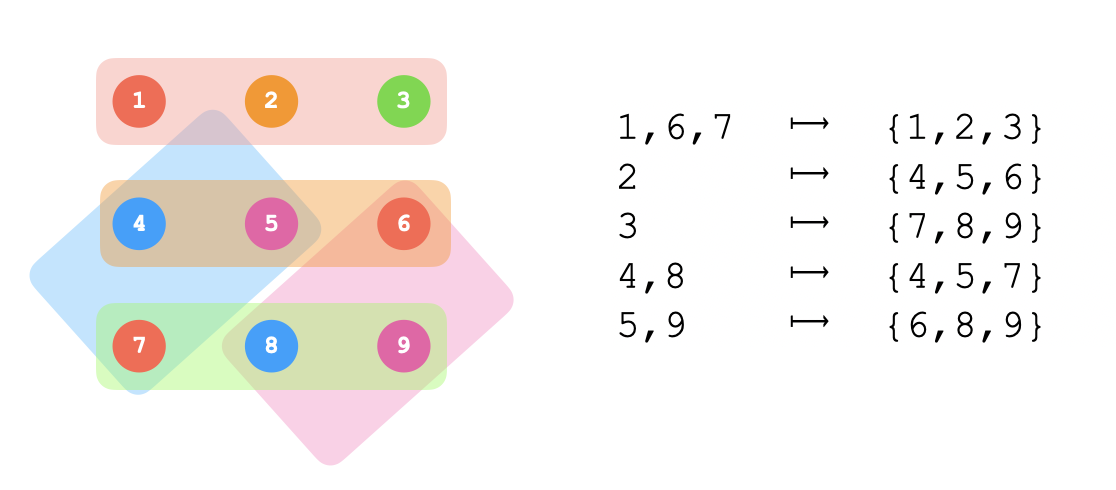

Here's an example of a central groupoid of order 9 that is not natural:

You can check for yourself that it satisfies the required property, namely that for each 3-element set of elements ${x,y,z}$, the collection of sets ${f(x),f(y),f(z)}$ comprises a partition of ${1,2,\cdots,9}$. Note that there are only two distinct partitions to chosoe from here.

We shall see that each element $\alpha$ of a finite central groupoid $C$ determines a "local coordinate system" for $C$, and that consequently $C$ must have a perfect square number of elements.

Let $\alpha\in C$ be an arbitrary element of a central groupoid. Let the set of left-images of $\alpha$ be denoted $\alpha\cdot C$, and let the set of right-images of $\alpha$ be denoted $C\cdot \alpha$. In a natural central groupoid of order $n^2$, the set $\alpha\cdot C$ would consist of all points of the form $(\alpha_2, -)$ and $C\cdot \alpha$ would consist of all points of the form $(-,\alpha_1)$, so that each would have precisely $n$ points. Although a non-natural central groupoid does not come equipped with such a global coordinate representation, it remain the case in these central groupoids that $\alpha\cdot C$ and $C\cdot \alpha$ have the same number of elements. In particular, we have the following bijection $\alpha\cdot C \simeq C\cdot \alpha$: To see that this is a bijection, let $x=\alpha\cdot x'\in \alpha\cdot C$ be arbitrary and observe that

Since $C$ is a finite set, this is sufficient to conclude that $g_\alpha$ and $g^{-1}_\alpha$ as defined are inverses.

Knowing that $|\alpha\cdot C| = |C\cdot \alpha|$, we are ready to prove that $C$ must have cardinality a perfect square, and in the process derive a "local coordinate system" for $C$ based on the element $\alpha$. To accomplish this, we can exhibit a very simple bijection between $C$ itself and the set $(\alpha\cdot C)\times (C\cdot\alpha)$, namely the mapping $x\mapsto (\alpha\cdot x, x\cdot\alpha)$ with inverse mapping $(y_1,y_2)\mapsto y_1\cdot y_2$. The fact that these mappings are inverses follows directly from the central groupoid law and the finiteness of the set $C$. This establishes immediately that $|C| = n^2$, where $n = |\alpha\cdot C| = |C\cdot\alpha|$.

We can also prove that a central groupoid $C$ of order $n^2$ has precisely $n$ idempotent elements, that is, elements $x$ satisfying $x\cdot x = x$. This property is easiest to prove using the matrix representation $M$ for the central groupoid. The rows and columns of $M$ correspond to elements of $C$ or nodes of the corresponding digraph $D$, and idempotent elements correspond to loops of the digraph, or diagonal entries of $M$. Hence the number of idempotents is equal to the trace $\text{tr}(M)$. This trace can be computed directly as the sum of the eigenvalues of $M$. Since $M^2 = J$, and $J$ has characteristic polynomial $(\lambda - n^2)\lambda^{n^2-1}$, meaning that $M$ has characteristic polynomials $(\lambda - n)\lambda^{n^2-1}$ and trace $\text{tr}(M) = n$.

There are precisely 6 central groupoids of order 9 up to isomorphism. It isn't difficult to enumerate them by hand with a bit of patience. But if we move on to the central groupoids of order 16, the number of possibilities explodes. (As far as I'm aware, nobody in the mathematical literature has successfully enumerated the 16-element central groupoids yet, even with computer assistance.)

The problem of determining whether two binary operations on finite sets of the same cardinality are isomorphic is in general very computationally intensive. For two sets of order $N$, there are $N!$ different bijections between the two sets, each of which is a possible isomorphism to be confirmed or ruled out. However, depending on the nature of the binary operation and its properties, the problem can sometimes be simplified considerably.

In the case of central groupoids, the idempotent elements can be used to simplify the process of checking isomorphism. We know that any central groupoid with $n^2$ elements must have precisely $n$ idempotent elements. As a consequence of this fact, the idempotent elements of any central groupoid must generate the entire central groupoid, since the sub-central-groupoid generated by those elements must also be a central groupoid with at least $n$ idempotent elements (namely the generators themselves). Hence, any isomorphism between two central groupoids is completely determined by its action on the idempotent elements. That narrows down the number of bijections that need to be checked from $N!$ to $(\sqrt N)!$. The latter still grows quite fast as a function of $N$, but for smaller values of $N$, this trick can be a huge help: for example, in the case of $N=16$, it's the difference between checking $16!\approx 2.1\times 10^{13}$ bijections and only $4!=24$. Note that this also simplifies the problem of finding the symmetry group of central groupoids, and it implies that the symmetry group of a central groupoid of order $n^2$ is a subgroup of $S_n$.

I've identified 3,471 nonisomorphic central groupoids of order $4^2=16$ using an algorithm that produces novel central groupoids by making small tweaks to existing ones. Unfortunately, I'm not sure whether my method produces all possible central groupoids of order $16$, but (purely conjecturally) I believe that it does. Furthermore, my code, written in Haskell, is not formally verified. (You can check it out in this Gist if you want, or you can explore this JSON data listing the central groupoids I found and some of their properties.) So any of my comments below about the results of this number crunching can be taken with a grain of salt.

One interesting property of central groupoids to consider is the symmetry group, that is, its group of automorphisms (bijective operation-respecting functions). As mentioned earlier, any isomorphism of central groupoids of order $n^2$ is determined by its action on the $n$ idempotent elements (since they generate the whole set), so it suffices to characterise how these automorphisms permute these elements. For central groupoids of order $16$, it is pretty easy to calculate automorphism groups. For the 3,471 nonisomorphic central groupoids that I found, here's the breakdown of symmetry groups. As you can see, the overwhelming majority have no nontrivial symmetries at all, but a few exceptional ones have more interesting symmetry groups.

| Automorphism group action | Number of central groupoids of order 16 |

|---|---|

| Trivial | 3254 |

| $\mathbb Z_2$ swapping one pair of idempotents | 136 |

| $\mathbb Z_2$ swapping two pairs of idempotents | 56 |

| $\mathbb Z_3$ | 8 |

| $S_3$ | 4 |

| $V$ acting intransitively | 5 |

| $V$ acting transitively | 2 |

| $\mathbb Z_4$ | 4 |

| $D_4$ | 1 |

| $S_4$ | 1 (just the natural one) |

Another interesting statistic: of the more than 3,000 central groupoids that I found, only 33 are self-dual, meaning that they are isomorphic to the central groupoid you get by reversing the order of the operation (or reversing the edges in the corresponding digraph, if you prefer). This makes self-duality a shockingly rare property.

A few more intriguing finds among the $16$-element central groupoids that I enumerated include the following: